Pathophysiology

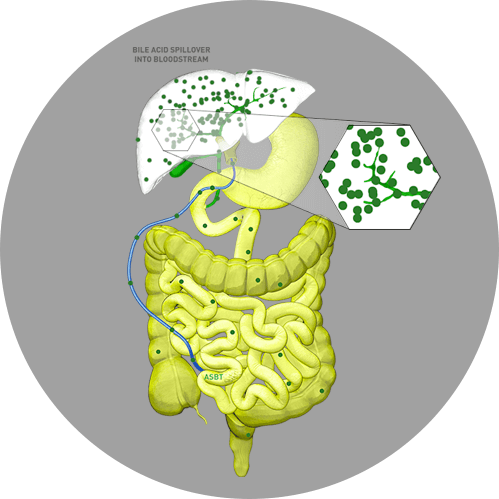

The main pathophysiologic characteristics underlying cholestasis in individuals with Alagille syndrome are abnormal development of intrahepatic bile ducts and bile duct paucity.1

The main pathophysiologic characteristics underlying cholestasis in individuals with Alagille syndrome are abnormal development of intrahepatic bile ducts and bile duct paucity.1

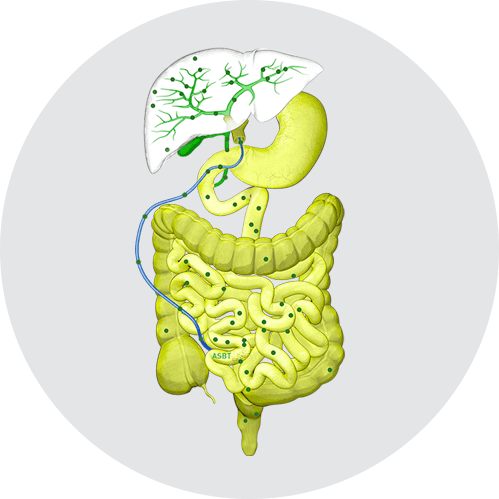

An important component of bile are bile acids, which help facilitate digestion and absorption of dietary cholesterol, triglycerides, and fat-soluble vitamins.2

Normally, bile acids are synthesized in hepatocytes and secreted in the bile via bile salt export pumps (BSEP) at the apical (canalicular) membrane. Bile acids then move through bile ducts to the gallbladder for storage and, later, for release into the small intestine to aid in digestion and absorption. Per cycle, up to 95% of bile acids are reabsorbed from the ileum via the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT), also known as the ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT), for return to the liver through the hepatic portal vein.1

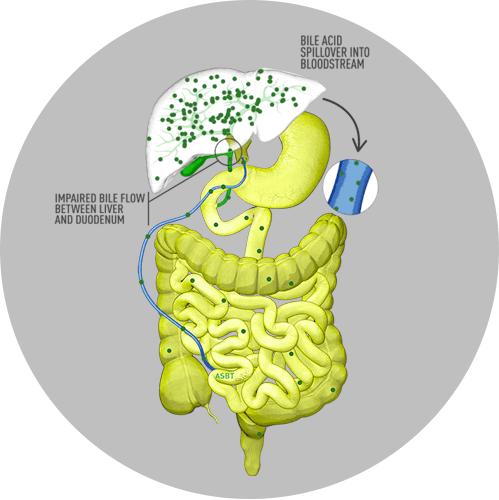

In cholestatic liver disease, the flow of bile is impaired at some point between the liver cells, which produce bile, and the duodenum. Bile acids, therefore, build up in the liver. This leads to liver injury and/or progressive liver disease, and, if left untreated, can result in fibrosis, cirrhosis, liver failure, and death. In addition, there is spillover of bile into the bloodstream, resulting in increased serum bile acids (sBA).3,4

In Alagille syndrome, specifically, the narrow, malformed, or reduced number of bile ducts results in bile buildup in the liver and subsequent clinical manifestations of the disease.5 In addition, enterohepatic reabsorption of bile acids from the intestine back to the liver may be enhanced or accelerated during cholestasis and can lead to the toxic accumulation of bile acids.1

This toxic buildup of bile acids can damage liver cells, leading to activation of fibrotic and inflammatory pathways that, ultimately, lead to liver injury.1

In Alagille syndrome, sBA levels are generally elevated many times the typical upper limit of normal.6 Elevated sBA levels have been implicated in pruritus via this hepatocyte toxicity. Hepatocyte membranes can be altered by detergent bile acids, which can result in hepatocyte contents (including pruritogens) leaking out into the bloodstream.7

Reducing sBA levels in patients with cholestasis is predicted to result in decreased liver damage.8

The most debilitating symptom of cholestasis in Alagille syndrome is intense pruritus, which is among the worst in any cholestatic liver disease.9

Driven by the increase in sBA, cholestatic pruritus is described as a severe, unrelenting itch.1 This unrelenting pruritus negatively impacts patients’ quality of life.10

Therapy-refractory persistent pruritus is an indication for liver transplant, even in the absence of liver failure.12

Patients who delay transplant when indicated for refractory cholestatic pruritus will continue to experience debilitating cholestatic pruritus and poor quality of life.13

Currently, there is one drug that is FDA approved to treat cholestatic pruritus in patients with Alagille syndrome.1,14

Alagille syndrome currently has no cure. The goal of medical management is to relieve pruritus and prevent end-stage liver disease (ESLD), prolong survival, and possibly even prevent the need for liver transplant.15,16

Cholestatic pruritus is often managed by liver transplant or other surgical interventions.6 There is a high burden of progressive liver disease in Alagille syndrome, with early profound cholestasis, and a second wave of portal hypertension and associated complications later in adolescence. Only 24% to 40% of patients reach young adulthood with their native liver.17,18

In a large-scale, international study of liver disease in children with Alagille syndrome (N=1433), 328 children with neonatal cholestasis required a liver transplant. For these children, the most common indications for liver transplant were intractable pruritus (n=161), growth failure (n=127), xanthomas (n=116), metabolic bone disease (n=16), and fat-soluble vitamin deficiency (n=3).18

The pruritus experienced by patients with Alagille syndrome is among the most severe in any chronic liver disease, negatively impacting physical and psychosocial health.1,13

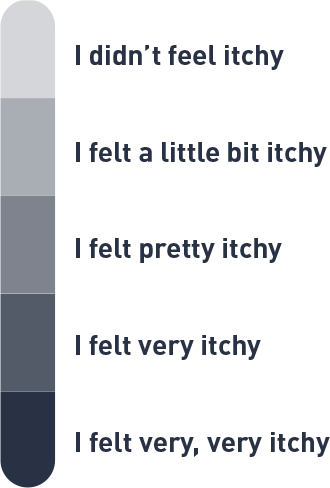

Due to a lack of pediatric itch assessments that meet current FDA patient-reported outcome (PRO) guidelines, the Itch Reported Outcome (ItchRO) tool—available as both a patient- and caregiver-reported outcome tool—was developed specifically for, and fully validated in, patients with cholestatic liver disease.20

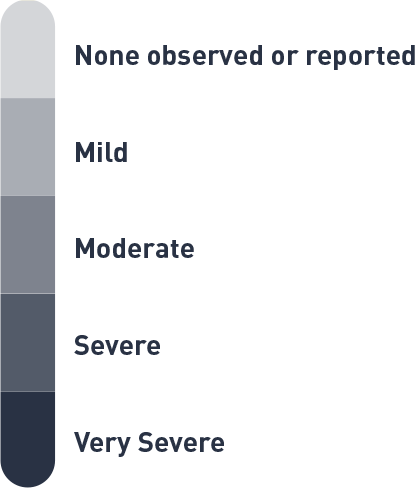

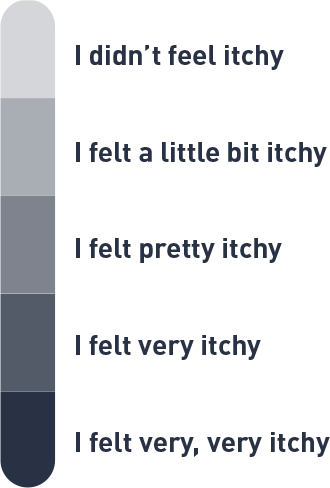

The ItchRO tool features a 5-point scoring system to assess the intensity of the itching16:

Move the slider to view the itch scale.

Move the slider to view the itch scale.

In practice, a caregiver is provided with a morning and evening ItchRO electronic diary16:

Based on observations or what your child told you about his/her itching, how severe were your child's itch-related symptoms (rubbing, scratching, skin damage, sleep disturbances, or irritability) from when he/she went to bed last night until he/she woke up this morning?

Based on observations or what your child told you about his/her itching, how severe were your child's itch-related symptoms (rubbing, scratching, skin damage, sleep disturbances, or irritability) from the time he/she woke up this morning until he/she went to bed?

A patient who is ≥9 years of age, on the other hand, is provided with morning and evening diaries that differ slightly20:

How itchy did you feel last night after you went to bed until you woke up this morning?

(Note: The following two items are exploratory and will not contribute to the ItchRO score. If the subject answered “I didn’t feel itchy”, the following will not be presented on the eDiary)

How itchy were you all day today from the time when you woke up until now?

(Note: The following item is exploratory and will not contribute to the ItchRO score. If the subject answered “I didn’t feel itchy”, the following will not be presented on the eDiary)

In addition to the caregiver- and patient-rated ItchRO, pruritus can also be assessed using the physician-rated CSS score.17

The CSS is based on a 5-point scale, where17,21:

These novel tools allow physicians to better assess the severity of itching in children with Alagille syndrome and other cholestatic liver diseases.